Jazz Guys

| by Myrah Valmyr

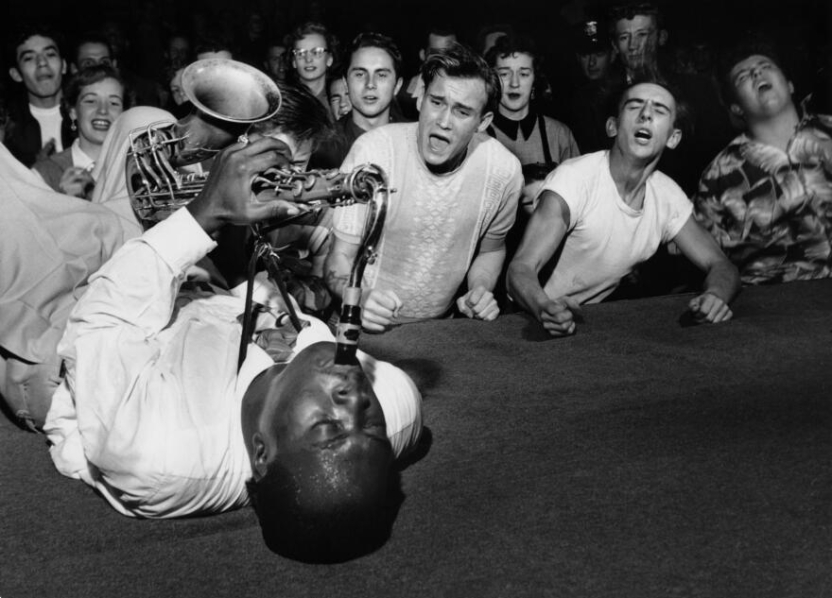

Big Jay McNeely photographed by Bob Willoughby at Olympic Auditorium, Los Angeles (1951)

A DISCLAIMER — Let it be known that in just about any space, I can, at will, make myself out to be the ‘Jazz Guy.’ I’ve done my time listening to a great deal of jazz, researching it, and playing it. I have been a bystander to the ‘Jazz Guy-ification’ teenage boys undergo in vulnerable spaces like liberal arts colleges and underfunded high school band programs. I have befriended them and will most likely befriend more. I’ve awarded them insurmountable levels of cognitive dissonance, nodding along to their recommendations, knowing they don’t want mine in return.

What is it about jazz that gets people all riled up? Jazz is a very calculated genre, molded by theory, technique, and the ability to listen between the lines. You can catch it, hold it, and own it. Inherently, jazz is all about breaking molds. Somewhere along the way though, we lost the plot, and it has become a game of checkpoints to reach and standards to uphold. Oh, a Jacob Collier archetype might inquire, you can’t play D minor pentatonic scale? For whatever reason these guys have elected themselves next-of-kin to Charlie Parker or Dizzy Gillespie. Do THEY know you’re their kin? I’ve got to hand it to them; these guys are damn good gatekeepers. What does this mean, you may be wondering of this elusive ‘Jazz Guy’ I speak of. Who is that? I’m sure you’ve got an idea already. If not, it goes as follows:

Friday night. December 2024. Sophomore year. Numbing cold, uniquely Vermont, eats at a few party stragglers and I on a porch. To my right, a date, chatty and elated. To my left, groups of two or three bound by a circulating cigarette. Straight ahead, a man I’ve never seen before, joining us before I register him. From there, the three of us embark on a brash, stupid, and simple voyage: conversation about music. Pleasant, no? Even better, this mystery man clues my date and I in on a prolific, perhaps understated, maybe even underground musician.

Oh, John Coltrane, I respond. Yeah, he’s great.

The man continues. I’ve been getting into jazz recently. You know the song Giant Steps? And the story behind it? Man, the pianist just like totally loses it, but Coltrane is just blazing through, leaving him behind…

There are jazz musicians who dedicate themselves to playing, getting good because of passion, appreciation, and attention. There are also those who do it to appear as being passionate, appreciative, and attentive, a cloak of formidable cool. I believe that most musicians are well intentioned and look at art with complexity, allowing challenge and hard truths to unveil themselves through the art. I also believe that Jazz Guys rub shoulders with something sick and hope it’ll leave a mark. There’s a part of them that think they’re better than the rest of us, that their music (“their”) is the best music. I find that these guys are almost always white. This adds a layer to the whole musical superiority complex that really gnaws at me. It’s a funny scene: two white guys talking around a Black girl about jazz. Us on that porch could have been an episode of Atlanta (re: Season 1, Episode 9: Juneteenth). Wasn’t Whiplash a movie about two white guys trying to out jazz each other, almost to death? And they did all that for (white) jazz drummer Buddy Rich’s holy spirit.

I keep from looking at my date, carefully constructing a response, one that is genuine and unironic, all while making clear I understand what this stranger is talking about. Maybe even more than he does. This is a Jazz Guy, I contend. To my right, I remember, is, surprise, another Jazz Guy. Maybe someone will drop their cigarette and the porch will explode. Now, of course, I am stuck listening to, what undoubtedly is, the transcript of a Vox video about this exact song and its lore (re: The most feared song in jazz, explained). What’s baffling is that he offers nothing new. What’s odd is that there’s not a lick of conviction in his words. His locution is technical. Formulaic opinion. It’s cruel in the way that, give or take a few words, we might as well have been talking about the weather. He moves in on Miles Davis. He is not taking questions or comments at this moment. This goes on before others come in and break up our, uh, cultural exchange of sorts.

Now, I know I am at risk of sounding pretentious while I criticize pretension. But still. Music superiorly complexes come in all shapes and forms, yet some are more tolerable than others. To be an electronic or indie rock devotee, shit, even a DJ, is one thing, but whatever mix of measured abstraction and arrogance that Jazz Guys put other musicians up to, is another. I have yet to meet anyone so confidently talk at you about a genre as if it fell out of their ass one morning, fished it from the toilet bowl, and mounted it on their wall or keep it in a trophy case. I am no stranger to rooms of brass instruments and egos, full of eager lips, and wood-pressed tongues,tongues taking solo after solo, raising trumpet in triumph, adding trill and crescendo. Later, these tongues are slipping passive aggressive comments about you and your tone or something else wrong, valve oil and spit dripping from their horns. Classical music buffs aren’t any better. They might be worse. We’ll put them at the other end of the horseshoe.

Let me, just this once, push back on Bill Evans’ and Chet Baker loyalists. Let me plug my ears to the track rewinds and the honesty in the drums, or, the zest of the tenor. Why is it that you are telling me what jazz is and how to listen to it? Why do you hear something that I don’t? And please, don’t tell the let people enjoy things crowd on me. If it were my way, everyone would be listening to jazz. I love it. It’s visceral, pulsing, rife with pain, severe and blinding; a type that should make a person ridged, unliving. Yet, jazz pioneers who gave their whole hearts, bodies, and minds to the music are the opposite. They are moving, sweeping figures, bent and burning on stages, in alleys, in and out of the light. What release! Sweet transcendence of hurt into air into sound into hope. They would play to themselves, empty rooms, and the few people who would give a shit forever. And they did. Until, of course, their sound was deemed palatable enough to be sold. A genre so dense will attract an array of people to laugh with, and to argue with, and sometimes against. At this point, I am at risk of sounding pretentious, and I’m okay with it.